Food Security Nobel Peace Prize:

Comparing Brazil and the World

The news that the UN's World Food Program was awarded the 2020 Nobel Peace Prize puts the topic of food insecurity back on the agenda. In this respect, Brazil occupies a prominent place, both from the point of view of its role as a food supplier country and the challenges Brazilians have to face regarding food security.

The Hunger Nobel Prize

It was not yet this time that a Brazilian received the Nobel Prize but we are getting closer to it. Brazil is the homeland of Josué de Castro, author of Geography of Hunger in 1943 and president of the FAO Executive Council, in addition to being the homeland of José Graziano, its last director.

Evidence on hunger and food insecurity challenges those who believe that hunger is a problem of the past in Brazil, a country known as “the World’s Farm” for its global food producer role. Food insecurity, which had fallen from 34.9% of households in 2004 to 22.6% in 2013, rises again, reaching 36.7% in 2018 according to the Brazilian Household Budget Survey (POF / IBGE). FGV Social’s research using Gallup World Poll data shows that it remained high in 2019. Characterizing the worsening perceptions of having money for food, i.e. food insecurity, Brazil had 17% of the population agreeing that they lacked money for food in 2014, which put the country in the No. 36 position in a list of 150 countries. Recently, 30 % of Brazilians claimed not having enough money for food in 2019 - corresponding to position 82 among 145 countries.

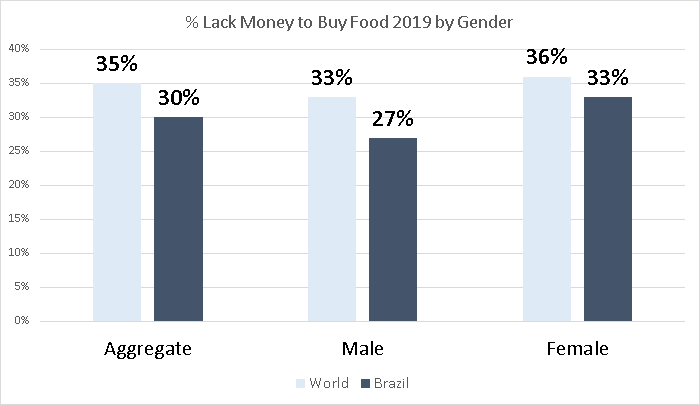

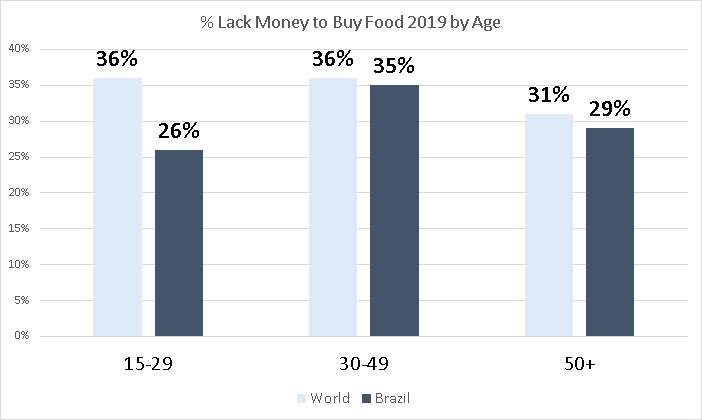

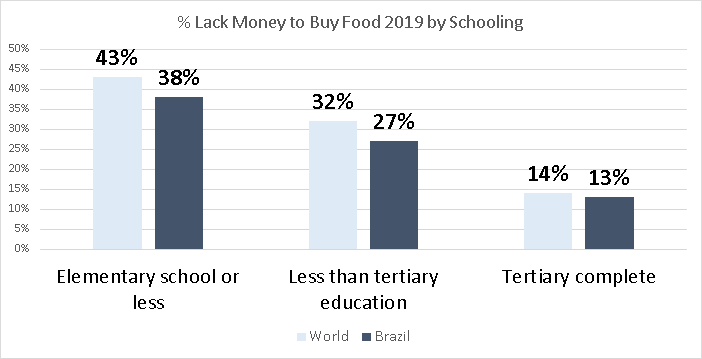

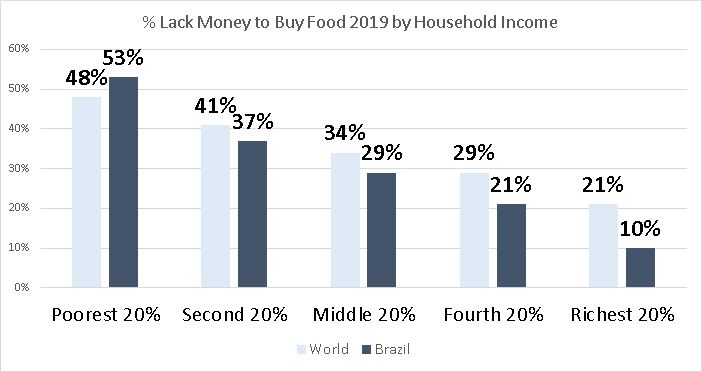

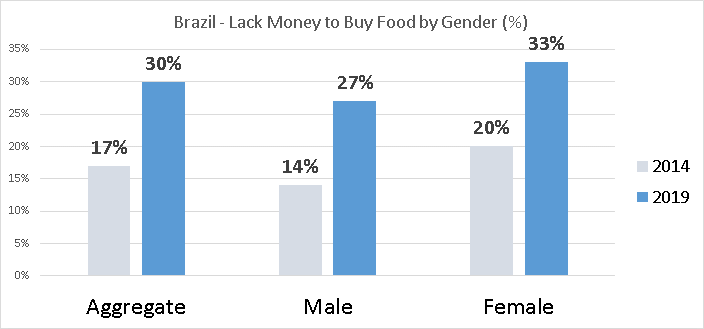

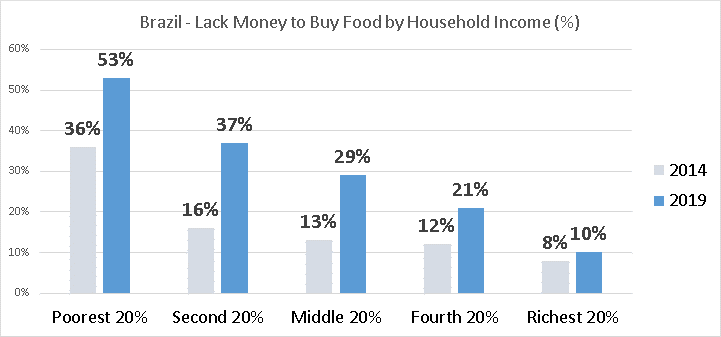

In order to capture the Brazilian inequality of food insecurity in 2019, 53% of the citizens among the poorest 20% Brazilians claimed not having enough money for food, while only 10% among the richest 20% Brazilians were in the same situation. In the world, the figures were 48% of the individuals in the poorest 20% and 21% in the richest 20%. In other words, our poorest individuals today face more food insecurity than the world’s poorest citizens, while our richest ones are in the exact opposite situation. We have also collected data on food insecurity by sex, age, income etc.

Brazil and the World

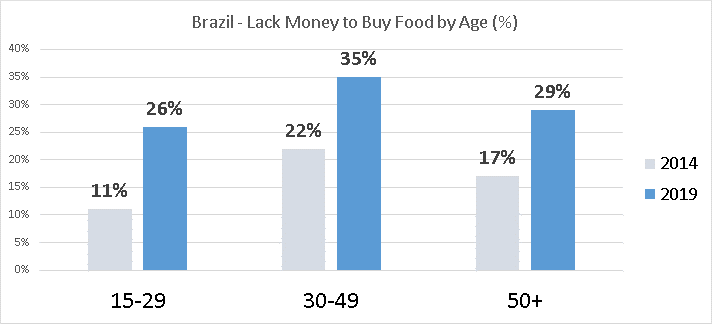

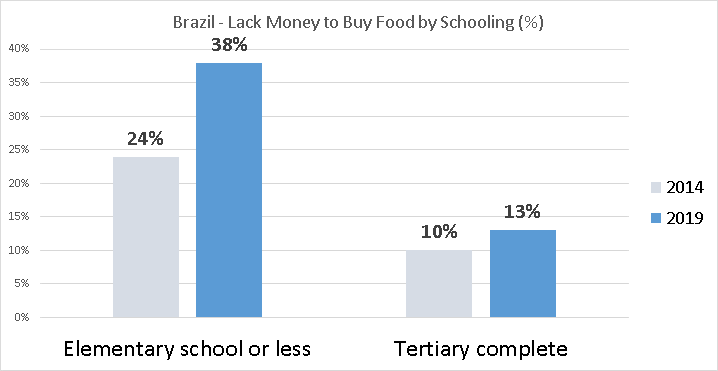

Looking at the latest photograph of Brazilian and global food insecurity in 2019, we find that food insecurity is slightly less pronounced in Brazil than in the world. It affects more women than men both in Brazil and in the world but especially in the former. As well as for middle-aged people, who tend to have children at home, generating consequences for the future of the country, since child malnutrition leaves permanent physical and mental marks on the lives of individuals. Poorer and less educated groups are, as expected, more subject to food insecurity but much more here in Brazil than elsewhere. Brazil, a country known for its high income inequality, and recognized for its large-scale production of food, cannot isolate its most vulnerable citizens from the fear of hunger.

Brazil and the World - 2019

Source: FGV Social/CPS based on the Gallup World Poll microdata

Source: FGV Social/CPS based on the Gallup World Poll microdata

Source: FGV Social/CPS based on the Gallup World Poll microdata

Source: FGV Social/CPS based on the Gallup World Poll microdata

The Return of Brazil to the Hunger Map (2014 to 2019)

Now looking at the changes in Brazilian food insecurity between 2014 and 2019, a period in which the country has returned to the UN Hunger Map. The share of Brazilians who claimed not having enough money for food money has risen from 17% to 30%. The variation for men and women is also 13 percentage points. But it is proportionally higher among the poorest, the least educated, and the youngest, which coincides with the groups that already were the most vulnerable, in addition to being the groups who lost relatively more income during the great Brazilian recession followed by a slow recovery from 2014 to 2019. Income inequality, whether vertical (between people) or horizontal (between social groups) go hand in hand with food insecurity.

Brazil - 2014 x 2019

Source: FGV Social/CPS based on the Gallup World Poll microdata

Source: FGV Social/CPS based on the Gallup World Poll microdata

Source: FGV Social/CPS based on the Gallup World Poll microdata

Source: FGV Social/CPS based on the Gallup World Poll microdata

We present below fly-over maps and time-series charts that allow the reader to compare Brazilian insecurity with that of over a hundred other countries.

Interactive maps and charts (%) Not enough money for buying food (Total Population)

Maps- https://cps.fgv.br/en/lack-money-buy-food-total-population-2005-2018

Chats - https://www.cps.fgv.br/cps/bd/graficos/Food/Lack-money-to-buy-food-Total-Population-2005-2018.htm

Food Security: Recent Changes and Global Overview

Brazil, a country known as the "Farm of the World" because of its vast agricultural sector, is also the land of Josué de Castro, author of “The Geography of Hunger” in 1943, and Betinho, creator of the NGO Ação da Cidadania, which fights against hunger and misery, more active than ever in the midst of the pandemic. Brazilians attach high importance to this theme, losing only to health and education among the 16 themes related to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Hunger raises more concerns here than in other countries. There is a reason for that. Brazilian feeding programs are associated with the prevalence of chronic diseases, low school performance, low labor productivity, among other deleterious effects tested.

The evidence on the evolution of food security and insecurity presented in the Family’s Budget Survey (POF/IBGE 2017-18) challenges those who believe that hunger is a thing of the past in Brazil. Food insecurity, which had fallen from 34.9% of households in 2004 to 22.6% in 2013, has risen again to 36.7% in 2018.

In order to better understand the direct causes of these changes in food safety, it is worth resorting, in objective terms, to ours previous researches on extreme poverty. We used the poverty line of U$S 1.25 day PPP (adjusted by Purchasing Power Parity) of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) that roughly matches the income criterion for receiving the basic monetary benefit of the Bolsa Família program (Family Grant), which is about 90 Brazilian reais per capita per month. The fall in food insecurity from 2004 to 2013 was accompanied by a reduction in extreme poverty of 44.7% in Brazil. In the period between 2014 and 2019, we observed an accumulated increase in extreme poverty of 67%, with registered increases in this income-based measure of extreme poverty in all years, including the latter. If food insecurity first fell and then grew, it is because extreme poverty has presented movements in the same direction. In recent years the poorest Brazilians have been suffering the most. While the initial period was marked by the expansion of well-targeted conditional cash transfer programs, in the most recent period we have made a fiscal adjustment on the shoulders of the poor by dehydrating the Bolsa Família program. Subjective measures of hunger have been walking hand in hand with extreme poverty estimates, whose movements were dictated by social policies. In a phase of scarce fiscal resources, social programmes aimed at the poorest individuals among the poor must be put back on the agenda.

Before they attack the messenger, we have noticed the same pessimism in international evidence about Brazil, already including 2019. This time and geographical extension of theme (food security), in addition to its detailing, are the main contribution of this note. To compare Brazil with other countries in the world, we use the microdata of the Gallup World Poll over seven consecutive two-year periods, from 2005/2006 to 2017/2018 and then 2019 to complement the series. In short, food insecurity falls from 20% in 2005/2006 to 18% in the 2011/2012, and then rises to 30% in 2017/2018, which is consistent in terms of period and deadlines with the last POF-IBGE evidence. This same level of 30% is maintained in 2019. In other words, the data suggest that the movements identified in IBGE’s surveys are robust and that the increase observed until 2017-18 was maintained in 2019.

Characterizing the worsening of the perceptions regarding lack of money for food: we had 17% of the population in this group in 2014, which placed the country in the no. 36 of 150 countries. In 2019, the share of Brazilians declaring not having enough money to buy food jumped to 30% - corresponding to the no. 82 position of 145 countries. In order to capture the tupiniquim inequality of the lack of money for food in 2019, we observed that 53% of the poorest 20% Brazilians were in this group and only 10% among the richest 20% Brazilians. In the world the numbers were 48% of the individuals in the poorest 20% and 21% in the richest 20%. That is, our poorest people today have more food insecurity than the poorest citizens in the world, while our richest have less problems of food insecurity.