Agenda for Social Advances

Neri gives the inclusive growth recipe for Brazil. For economist Marcelo Neri, director of the FGV Social, increasing productivity and fiscal reform are essential for the country to grow again along with social progress.

(Interview published by Jornal do Brasil in March 2018)

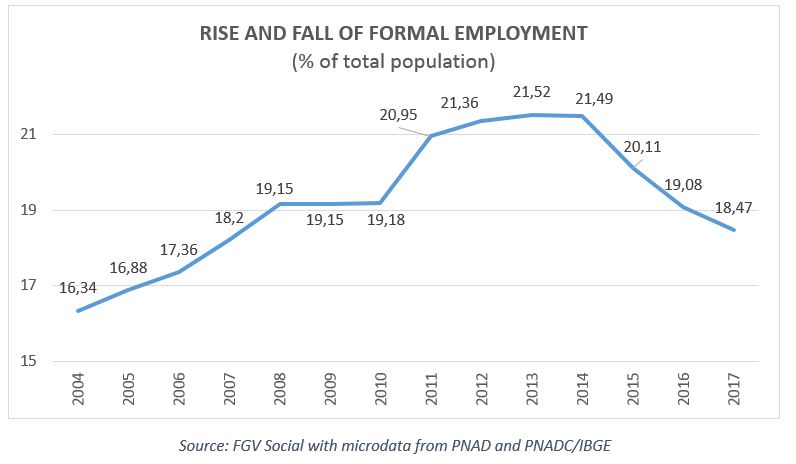

For the Director of the FGV Social, economist Marcelo Neri, it is necessary to admit that part of the gains achieved in the last years must be given up for the country to leave the crisis and grow again in a sustainable way. Last decade, Neri coined the term "new middle class" to refer to the expansion of Class C. Today he has a clearer vision: "what facilitated the rise of this class was the formal employment, which opened the doors of credit and consumption to a mass of workers”. Unfortunately, the recession and unemployment created a descent on the roller coaster.

He defines the current decade situation into two distinct periods. After the mini GDP in 2012 and the stagnation of the economy until 2014, the year of re-election was the peak of the rise, with the welfare rate growing from 6% to 7% a year. "Then came the disgrace" and by the middle of 2016, the bottom of the crisis, the country had lost almost three million formal jobs. In the two years of sharp decline in income (2015 and 2016), there was an increase in inequality. What had not happened here since 1989, that holds the Brazilian record of inequality.

That is why household consumption grew in the end of 2017 less than expected. Brazilian mean income is growing again, but is more concentrated, which does not favor consumption. With the expectation of GDP growth for 2018 at 3%, Neri says that income is already growing: "the current average rate is 3.6% higher than at the beginning of 2017." However, the result is basically due to falling food prices and the favorable interest shock of 2016. In spite of the real income recomposition, inequality also began to grow again.

Neri maintains the enchantment with the capacity that the country had before the crisis to grow and, at the same time, to diminish the social inequality. "That was the beauty of the Brazilian case. What we have today is a better country, but maybe it is not the real one", he mourns. The country has forgotten to adjust the economic agenda to the process of social advancement, he adds. Income has grown, but productivity has not. Worst, it has advanced more on the classes of less skilled workers, a group that, by the world’s economic logic, may be forced to lose the previous income gain because it can not be more productive in the short term.

The alternative is that other segments of society are willing to increase their contribution to avoid the setback that can make the country again more unequal. For now, it is not what is happening. "We are going towards the wall, people are warning us, and we continue as if there is no tomorrow," he mourns. In a conversation with the JORNAL DO BRASIL, Neri said that Brazil's biggest challenge today is to reconnect the social and economic agenda and the continuity of the reforms. For him, the country’s two major economic issues are productivity and fiscal adjustment, which need to be resolved. "There is a lack of basic economic responsibility to make policy innovations a lasting good news," he says. Main excerpts from the interview:

Advances. We have the view that Brazil has not advanced much in recent years and that, due to the recession and unemployment, from the social viewpoint, it has advanced a lot and not in an unsustainable way. If we take the map of human development, in the world, only by the colors, we see that Brazil had African colors 20 years ago and there was a great social transformation. The problem is that we have had the social agenda disconnected from the economic agenda. The social was good, but we did not have the economic responsibility to do social security reform, and to think about productivity.

Education. Education has advanced with low quality. We have increased access to school positively. In 1990, we had 16% of children aged seven to 14 out of school. Today we have less than 2%. We increased schooling, but productivity did not. In 1980, Brazil's productivity was equal to that of Korea. Today it is one-third for several factors: schooling, lack of connection with the economy, business environment, lack of engineers, etc. Brazil has followed an agenda (that has its merits) of citizenship education, not productivity. The social agenda is disconnected from the economic one.

Social Security. Life expectancy has increased a year every three years, but we didn’t do a social security reform. We spend 13% of GDP on social security and Japan, the longest-living nation in the world, spends 10%. With the aggravation that we will multiply by five our population of elderly people in in 50 years.

Minimum wage. The minimum wage is seen as the social policy, and is used to index all social programs, from Social Security to unemployment insurance, with the exception of Bolsa Familia. This creates a tax stiffer effect. It has social inclusion impact, but it costs a lot. And we're going to have a cumulative demographic impact. In addition to spending more on social security, with 86% of benefits equal to the minimum wage. And it will increase more in the future.

Research and Development. We participated in a R & D research in Latin America. Brazil has an enviable expenditure, it is almost equal to that of Spain. Only it is not effective. We do not have the money rich countries have, even as a proportion of GDP, but for countries of our level we spend more. It just lacks connection with economic practice. We increase academic output, but not the number of patents.

A policy for services. When we talk about economy, we talk about several sectors. The industry has a productivity problem. In agriculture, we are the very farm of the world. We have achieved several important advances, in agriculture and mining, with Embrapa, Petrobras, pre-salt and other companies. Brazil has this vocation and productivity grows. The largest employer in Brazil is the services sector, which accounts for about 70% of GDP and for most jobs. However, we often talk about the need for industrial policy, agricultural policy. There is no talk about service policy. Deep down, we are moving the dog's tail and not the dog.

Wrong policy. Brazil has made industrial policy, but wrong. It made all that intervention at the time of the crisis, with the public banks. However, it was kept for longer than it should and generated a very large fiscal imbalance because, as the interest rate is high, any deficits it creates, a snowball costs. Giving benefits to sector champions is expensive.

Inequality. In Brazil, income grew stronger at the base. It was the beauty of Brazilian growth. In most countries, those who have more education have a bigger increase in income. In Brazil, the number of people with more education increased, but the winners were people with low schooling. People who were employed in construction, in domestic employment had, by the adjustment of the minimum wage, an extra income gain, which is part of the country's inclusive social growth.

Step back. Maybe it's not just a little step back. In 2015, Brazil gave a strong readjustment to the minimum wage when there was talk of reform. It was a counter-reform, which did not make the slightest sense. Any step back, has acquired right, determinations of the Constitution, such as that says that the real value of pensions has to be maintained. It does not define what the indexer should be (INPC, GDP increase) but the reference has to be maintained. So we are going towards the wall, people are warning us, and the country continues as if there is no tomorrow.

Economic crisis. The critical point of the crisis was mid-2016, with income falling 6%, under stagflation: high inflation and high unemployment. Then, the Central Bank did its homework, with the help of the super crop, inflation fell and there was a gain (of income). Income from work is already growing by 3.6% (quarter on quarter) to the 3% growth expectation of GDP. But inequality is increasing. This disrupts the economy, recovery and social well-being. And it can generate political trouble as well.

Employment. The hero of the resumption was the Central Bank. But now there will be no other disinflation ahead. To generate income growth, it will have to be by the fall of unemployment, the immediate challenge. In the long term, Brazil's problem will not be unemployment. It will be the lack of manpower, because the demographic bonus is ending. The case is more serious in Rio, where the apex of the demographic bonus was reached in 2016. Here, demography is already playing against us. The Active Age Population (people between 15 and 65 years) as a proportion of the population is already falling in Rio. In Brazil, begins to fall in 2023 in a significant way.

Rio de Janeiro. There are three Rios: the state, the metropolitan region and the capital. The crisis first reached the periphery, in the Baixada Fluminense, and now it has good news. There, income and employment are already starting to recover again. The municipality of Rio was the Brazilian capital that grew most until the middle of 2016. Then it fell into the abyss. It came from 50 years of decay, but reached its peak in the second quarter of 2016. It was the capital that grew the most in the 27 months before the Olympics. We climbed on Olympus and plunged into the precipice, in free fall. This is a problem of Rio: always dies at the end of the movie either someone kills us or we commit suicide. We have difficulty coping with success.

Political cycles. Every election year is expansionist. You announce you are conservative and expands, creating a surprise. Therefore, 2018 will be better and 2019 will be worse. It is the political cycle. There was only one election in which the income did not fall in the following year: 2007. In 2007 and 2010 there was no economic adjustment after elections. We piled up disequilibrium and, in 2015, we had an inverted cycle. (The government) said it would be expansionist and placed Joaquim Levy as Finance Minister. It was an inverted political cycle, which caused great disaster.

Future agenda. The youth agenda is difficult all over the world because young people are not understood by their parents, by themselves, let alone governments, at any level. It is where we are losing the war, with violence, traffic accidents, drugs, prisons, early pregnancy. And the most serious is that the youth agenda is a state problem: violence, employment, traffic, prisons are all state agendas, and they are much more bankrupt than municipalities, and will lose revenue because the activities generated by the new economy, like those of Uber, will go to the municipalities. It lacks coordination on a vital issue for the future of the country.

![]() Interview published by Jornal do Brasil in March 2018 (In Portuguese): https://www.cps.fgv.br/cps/bd/clippings/uc049.pdf

Interview published by Jornal do Brasil in March 2018 (In Portuguese): https://www.cps.fgv.br/cps/bd/clippings/uc049.pdf